Indeed, the blog is still quite dead, but I thought I'd post something of some small interest should anyone happen to stumble across here again (and, not to mention, just for the hell of it). This is a short research paper I composed on a topic I've been turning over in my head for some time now, and one that I thought might be of some small interest to the old readers... of course, it's quite doubtful that anyone should come around here again, but if so it would be interesting to hear any thoughts/opinions/death threats anyone might have. Huzzah! Enjoy.

P & ¬P (Nature of the Divine)

When first reading the Bible, one might be quite astounded to discover exactly how common are its inconsistencies and self-contradictions; indeed, from its very beginning the disparity between specific verses, the clashing of ideas, and, perhaps most significantly, contradictions within the very nature of God, become quite apparent and, to some, perhaps a bit troublesome. Clearly, were it to be read from a strictly logical perspective (as history rather than scripture, we could say), it could quickly be dismissed merely as the incoherent, superstitious ramblings of various Hebrew (and later Christian) madmen over the course of their turbulent history. Yet for all this, biblical contradictions throughout the scripture’s entirety have survived various revisions and canonizations and remain to this very day. To what end, then, do these inconsistencies there remain? Why didn’t those men who canonized the scripture, men who had devoted their lives to the religion based thereupon, revise the text so as to protect it from any such criticism? Surely such glaring inconsistencies could not have escaped their educated scrutiny. Therefore, we must conclude that these contradictions were, in fact, intentional. Though the reasons for this are not quite so clear, I shall explore, in this paper, the idea that these contradictions function to characterize God (and so, vicariously, all reality) as transcendent of the logical entailments that would render such contradictions impossibilities, thus establishing his ultimate divinity and making the universe utterly unfathomable through other, more mundane channels.

Of these contradictions, those first encountered serve to lend the divine aspect of ambiguity to biblical history through the order of events presented therein. As perhaps the most apparently inconsistent accounts in the scripture, the two versions of the creation myth serve quite early to confound the literal reader. According to Genesis 1,

God said, “Let the earth bring forth living creatures of every kind: cattle and creeping things and wild animals of the earth of every kind.” And it was so. God made the wild animals of the earth of every kind, and the cattle of every kind, and everything that creeps upon the ground of every kind… Then God said, “Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness; and let him have dominion over… [all the animals].” (Genesis 1:24-26)

Though here the precedence of beast before man is quite apparent, Genesis 2 brings forward a conflicting account in which:

The Lord God said, “It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him a helper as his partner.” So out of the ground the Lord God formed every animal of the field and every bird of the air and brought them to the man to see what he would call them; and whatever the man called every living creature, that was its name. (Genesis 2:18-19)

One need not be a logician to notice that there is some disparity between these two passages. In the former, it is made quite clear that the “living creatures of every kind” were created first, and humankind afterwards that they might “have dominion over” those creatures already in existence. In the second passage, however, “every animal of the field and every bird of the air” was created after man; furthermore, it was for man that they were created (to serve as his helper), and man that gave names to these newly created creatures. Utterly unlike the first citation, beast was born as an afterthought to man, rather than man as ruler for existing beasts. Given that each account is essentially a sequential reversal of the other, it is clear that they are ultimately irreconcilable; thus, within these first two chapters of Genesis, the Bible wastes absolutely no time in introducing inconsistency.

Another very notable inconsistency in the bible is that of free will in the face of divine coercion and predestination. For the sake of our inquiry, let us use Van Inwagen’s definition in saying that in any given situation, a subject, S, acted freely if and only if “S can render [could have rendered] ‘…’ false, where ‘…’ may be replaced by names of propositions” (Van Inwagen, 189). For example, we can say that Abraham acted freely if and only if he could have actually sacrificed Isaac (which is to say that he could have rendered the proposition that he didn’t actually sacrifice Isaac false). In other words, free will means that at any given time an agent has more than but a single, predetermined course of action that he is capable of choosing (whether consciously grasped or not) . Let us assume, as well, that such free will is a prerequisite for moral responsibility (Pereboom, 31), given that moral responsibility is necessary for blame and subsequent punishment specifically of the agent (Pereboom, 40).

We see in the Bible, on various occasions, passages in full support of divine determinism (which is to say determinism by a deity rather than all-encompassing physical laws). In Romans, for instance, it was said that “for those whom he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son… and those whom he predestined he also… glorified” (Romans 8:29-30). Here it is stated, essentially, that God determines, before any action of the “agent,” whether they might ascend to heaven or suffer punishment in hell. The point is driven even further starting at Romans 9:11:

Even before they had been born or had done anything good or bad (so that God’s purpose of election might continue, not by works but by his call) she was told, “The elder shall serve the younger”… What then are we to say? Is there injustice on God’s part? By no means! For he says to Moses, “I will have mercy on whom I have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I have compassion.” So it depends not on human will or exertion, but on God who shows mercy. For the scripture says to Pharaoh, “I have raised you up for the very purpose of showing my power in you, so that my name may be proclaimed in all the earth.” So then he has mercy on whomever he chooses, and he hardens the heart of whomever he chooses. You will say to me then, “Why then does he still find fault? For who can resist his will?” But who indeed are you, a human being, to argue with God? Will what is molded say to the one who molds it, “Why have you made me like this?” Has the potter no right over the clay, to make out of the same lump one object for special use and another for ordinary use? (Romans 9:11-21)

With this, there could hardly be any better support for determinism within the Bible. Here, the future of the individual is determined by God’s election prior even to their birth (let alone free action), constituted for their purpose as a lump of clay is molded for its use, and powerless to question or to criticize he to whom they owe their existence. As God simply has mercy and compassion on whomever he feels the whim to give it, “human will or exertion” cannot possibly amount to anything; as Jacob, or Esau, or Pharaoh, man exists to fulfill the end for which God designed them.

Yet in the bible, we see many examples of agent-punishment; or, in more words, punishment, presupposing moral responsibility, to the end of righteously causing suffering, rather than for more mundane, utilitarian purposes like public safety or rehabilitation. Perhaps the best example anywhere of such punishment is that of eternal damnation to Hell, which, in Matthew, Jesus liked to speak of quite a bit. For example:

Just as the weeds are collected and burned up with fire, so will it be at the end of the age. The Son of Man will send his angels, and they will collect out of his kingdom all causes of sin and all evildoers, and they will throw them into the furnace of fire, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth. Then the righteous will shine like the sun in the kingdom of their Father. (Matthew 13:40-43)

Though not explicitly stating the purpose of punishment in Hell, this passage is quite telling nonetheless. Firstly, by referring to the punished as “causes of sin” and “evildoers” and comparing them to weeds, they are immediately portrayed as despicable and morally reprehensible; in essence, free agents worthy of blame. Secondly, by describing the conditions of the prison into which these “evildoers” shall be cast and the pleasant “weeping and gnashing of teeth” they shall get to participate in once there, it is readily apparent that a strong emphasis is being placed upon their sufferings. Though initially ambiguous, the purpose of this emphasis seems to be revealed when, in the next sentence, the righteous are depicted as happily shining like the sun in the kingdom of heaven, claiming their reward for piety whilst the sinners claim theirs for sin. Ending here, with everything in its right place, this passage implicitly states that the sinners are deserving of their eternity of suffering, that for choosing to do evil these free agents shall receive their just punishment as their actions by virtue of themselves called for it; punishment for the sake of punishment, as what other end could there be for a suffering without end?

From here, it is a small matter to prove the contradiction of free will and determinism. From the concept of Hell we see that there is, indeed, agent-punishment, and as such we must conclude that the Bible presupposes moral responsibility on these grounds. In turn we may conclude that, since there is moral responsibility, there is also free will, as determinism precludes moral responsibility (Pereboom, 31) and moral responsibility cannot exist without free will (as, otherwise, it is simply moral luck [Nagel, 28]). Thus, we are left with explicit arguments for determinism and implicit (though equally obvious) arguments for free will; since these are ultimately incompatible (Van Inwagen, 193), especially as here expressed, we can derive our contradiction.

Perhaps most importantly, however, the Bible contains many contradictions regarding the nature and personality of God. God’s all-encompassing mercifulness, for example, is harshly contradicted by his occasional display of incredible wrath and remorseless destruction. As stated in Psalms, “The Lord is gracious and merciful, slow to anger and abounding in steadfast love. The Lord is good to all, and his compassion is over all that he has made” (Psalms 145:8-9). While the God here described seems boundlessly merciful, and his love seems to extend to all (supposing, of course, that he made all), we encounter a slightly different account of him in Jeremiah when he says “And I will dash them one against another, parents and children together, says the Lord. I will not pity or spare or have compassion when I destroy them” (Jeremiah 13:14). Of course, this in itself is not a contradiction as it is entirely conceivable that a being could be both merciful and wrathful throughout the course of its existence, since one can most certainly undergo a change in disposition or philosophy that would allow for such an extreme reversal. The contradiction, however, arises in conjunction with the static nature of God, expressed well in James: “Every generous act of giving, with every perfect gift, is from above, coming down from the father of the lights, with whom there is no variation or shadow due to change” (James 1:17). It is from this that we derive our contradiction, for, since God does not change, he must simultaneously embody two entirely contradictory qualities: mercifulness and mercilessness.

Given that God is always unchanging, we may also prove a further contradiction in his nature regarding his predisposition to bring either war or peace. In Exodus, after the escape of the Jews from Egypt, Moses and the Israelites sang:

The Lord is a warrior; the Lord is his name.

Pharaoh’s chariots and his army he cast into the sea;

his picked officers were sunk in the Red Sea…

Your right hand, O Lord, glorious in power—

your right hand, O Lord, shattered the enemy.

In the greatness of your majesty you overthrew your adversaries;

you sent out your fury, it consumed them like stubble. (Exodus 15:3-7)

This passage, vaguely reminiscent, even, of violent Greek epic, portrays God as a deity of war; a “warrior,” as it is said, who shatters the enemies of his chosen people by the fury of his own right hand. Though well enough on its own, this passage looks a bit strange when in Judges, “Gideon built an altar… to the Lord and called it, The Lord is peace” (Judges 6:24). Strange, as well, is the end to the fifteenth chapter of Romans, when Paul says, “The God of peace be with all of you. Amen” (Romans 15:33). Surely he could not have been referring to the God of Exodus, the warrior who cast the armies of Egypt into the sea, the God of war who overthrew his adversaries in the greatness of his majesty; yet it was this that he was, and, as he does not change, it must be said that he is by nature peaceful and by nature warlike. Again, we arrive at a contradiction.

Even Elohim, one of the several names of this God, is itself a contradiction. The plural form of the Hebrew word Eloah, Elohim makes its first appearance among the first few words of Genesis, and, despite its plural form, is used throughout the Old Testament in reference to the one Hebrew God. The contradiction here is rather clever; plural in form, singular in meaning, the name of Elohim itself becomes a powerful allusion to the embodied contradiction contained throughout the entirety of the Bible and in particular the impossible being which it is meant to represent.

Upon further reflection, it seems possible that God, Himself, is nothing but clever contradiction. Simultaneously singular and plural, bellicose and peaceful, compassionate and merciless, God becomes a true, existent form of that which cannot possibly be. By embodying both p and ¬p (which is to say, in formal logic, that God embodies p and not p, where p is taken to represent some idea that God embodies or state in which he exists), by existing in two states which cannot possibly coexist in the same moment (as it is impossible for a contradictory sentence to be true [Bonevac, 28]), God is portrayed as the true realization of a logically necessary falsehood. In this, the figure of God transcends all human understanding; for what sense can we make of the statements that “it is raining and it is not raining” or “I exist and I do not exist”? If God is merciful and not merciful, if singular and not singular, then he cannot, by the deductive logic upon which man has come to depend in his dealings with the external world, exist; yet the Bible says that he does. Though it might be easy enough for someone to dismiss such a bizarre concept as nothing but a novel little nightmare engineered by a bunch of crazy, leprosy-afflicted, Egyptian outcasts (Tacitus, 2), one cannot, after giving the idea any small degree of thought, simply dismiss it as such; for what this God of contradiction represents is the greatest fear of man: the unknown (or better still, the unknowable) before which he is utterly powerless even to grasp at its nature. For the sake of convenience, let us call the state of transcendentally realized impossibility “divinity,” and conclude that it is through his existent self-contradictory nature that God stands in opposition to all human reason and embodies the divine.

Our other contradictions serve to further extend the terror of this divinity which so transcends all our now feeble human logic. As with the case of the creation myths, logical contradictions beyond our usual, sequential, a priori conceptions of time throw the entirety of history and our perception of time into question; if this impossible God exists, it is possible, then, both that God created man before beast and beast before man and that in this there is no inconsistency in this save the contradiction which exists solely in our flawed understanding of the world around us. As it is with history, so too, then, with ontology; for if it is possible that such an impossible being exist, divinity may be woven into the fabric of reality in such a way that strict determinism and libertarian free will may coexist without any conflict whatsoever, unless you choose to count that conflict which exists solely in the feeble minds of men. In such a way, all of our “known” reality, for the believer, is thrown into question as man’s entire system of grappling with the world is subverted by the existence of a being which quite simply should not exist according to all of its rules. Being thus rendered incomprehensible, the whole of reality may be consolidated beneath God, the embodiment of the irrationality which made them so in the first place, and the believer is left with a world governed entirely by that unknowable which his deductive reasoning could not begin to fathom.

Such conceptions of the divine are not so uncommon. In the quite possibly unpronounceable name of YHVH, we catch yet another glimpse of the transcendental nature of the divine; given that it cannot be pronounced God becomes even more incomprehensible, such that we cannot begin to grasp his being even by assigning to it a name which is within our power to speak. Saint Augustine, in his Confessions, also seems to characterize divinity as embodied by realized contradictions when he writes of God:

… stable and incomprehensible, immutable and yet changing all things, never new, never old… always active, always in repose, gathering to yourself but not in need… searching even though to you nothing is lacking: you love without burning, you are jealous in a way that is free of anxiety, you “repent” (Gen 6:6) without the pain of regret, you are wrathful and remain tranquil. You will a chance without any change in your design. You recover what you find, yet have never lost. Never in any need, you rejoice in your gains (Luke 15:7); you are never avaricious, yet you require interest (Matt. 25:27).We pay you more than you require so as to make you our debtor, yet who has anything which does not belong to you? (I Cor. 4:7). You pay off debts, though owing nothing to anyone; you cancel debts and incur no loss. (Augustine, 1, IV.4)

In this we can very clearly see our established theme of contradiction and the transcendent nature of divinity. Here, language itself “is being used to render its own insufficiency as the means by which God’s essence is to be expressed” (Lencek), thus rendering God impossible to understand as one might understand beings more earthly and corporeal. Never new yet never old, always active yet always in repose, God’s nature here remains self-contradictory; in his needless searching and gathering, his avaricious demands devoid entirely of avarice, his acceptance of payment by that which is already his and all of his actions in this passage emphasize an utter strangeness in the doings of Augustine’s God that suggest further contradiction not only in divine nature but in divine action. Contained, as well, within this passage are hints at the utterly bizarre ontological nature of divinity (which, as you may have guessed, defies logic); Saint Augustine’s description of God as “immutable yet changing all things,” though perhaps not intuitively indicative of transcendence, almost certainly refers to the same principle of divinity which Saint Thomas Aquinas outlined the first (the argument of causality) of his Five Ways (his famous arguments for the existence of God), which states,

Anything which is moved is moved by something else… To cause motion is to bring into being what was previously only able to be, and this can only be done by something that already is… Now the same thing cannot at the same time be both actually x and potentially x, though it can be actually x and potentially y: the actually hot cannot at the same time be potentially hot, though it can be potentially cold. Consequently, a thing which is moved cannot itself cause that same movement; it cannot move itself. Of necessity therefore anything moved is moved by something else… Now we must stop somewhere, otherwise there will be no first cause of the movement and as result no subsequent causes… Hence one is bound to arrive at some first cause of things being moved which is not itself moved by anything, and this is what everybody understands by God. (Davies, 29)

Transcendence of the bounds of logic, then, is entirely necessary for the unmoved mover which Aquinas means to paint as God in this argument. By his assertion that every movement in state from x to y is set into motion by something external to the object in question, it then stands to reason that there occurs at the beginning of this otherwise endless causal chain some ontologically strange “thing” that that is capable of effecting change without itself changing, as there is nothing of causal precedence that can effect in this prime mover any such change (since otherwise, as the argument clearly states, “there will be no first cause of the movement and as result no subsequent causes,” denying that there is any ever change in the world). Noting that there is change in the world, this argument directs one to conclude that there must, indeed, be something in (… and/or not in) the universe that defies the logic that tells us that change must be effected by change which, as a consequence, we cannot grasp.

All of this, then, seems to be the glorious end to which biblical inconsistencies remain. Through contradiction – historical, ontological, divine, or otherwise – the scripture manages to create, foster, and bring into realization fundamental doubt in the deductive human logic praised by Greek philosophers as being man’s only means of grappling with the external world, thus subverting the understanding of reality based solely thereupon and rendering everything unknowable through such means; in so doing, it also establishes a more sufficiently all-encompassing, though ultimately unfathomable, universal order within which all is subordinated to the embodiment of logically transcendent contradiction that is God.

Bibliography

Augustine. Confessions. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Bonevac, Daniel. Deduction: Introductory Symbolic Logic, 2nd Edition. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2003.

Davies, Brian. The Thought of Thomas Aquinas. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Lencek, Lena. “This Self that Thinks.” Reed College, Portland. 21 April 2006.

Nagel, Thomas. Mortal Questions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

The New Oxford Annotated Bible. Michael D. Coogan, ed. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.

Pereboom, Derk. “Determinism Al Dente.” Noûs 29. 1995, pp. 21-45.

Tacitus, P. Cornelius. The Histories.

Van Inwagen, Peter. “The Incompatibility of Free Will and Determinism.” Philosophical Studies Volume 27. 1975.

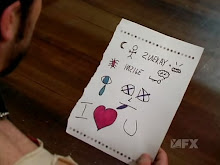

It's a bit hard to blog when one has absolutely no idea what to blog about, let alone blog well when one doesn't know the purpose of his blog in the first place. Possible solutions: devise a post giving this blog a purpose (which would likely be really long and contrived and ultimately change the idea of the blog into some half-assed, grandiose bullshit), dive into it anyway without a clear goal (which would be a nice little show of spontaneity and spur-of-the-moment sincerity, but, in the end, would end up being crude, unfocused, and ultimately uninteresting), or post some bizarre picture for no good reason and give up until I get a half-good idea. I bet you'll never guess what I picked!

It's a bit hard to blog when one has absolutely no idea what to blog about, let alone blog well when one doesn't know the purpose of his blog in the first place. Possible solutions: devise a post giving this blog a purpose (which would likely be really long and contrived and ultimately change the idea of the blog into some half-assed, grandiose bullshit), dive into it anyway without a clear goal (which would be a nice little show of spontaneity and spur-of-the-moment sincerity, but, in the end, would end up being crude, unfocused, and ultimately uninteresting), or post some bizarre picture for no good reason and give up until I get a half-good idea. I bet you'll never guess what I picked!